Europe is often seen as a global benchmark food security and healthcare. Yet beneath this perception lies a a less visible but widespread issue: micronutrient deficiencies or “hidden hunger.” Despite abundant food supplies, many Europeans do not get enough essential vitamins and minerals – iron, iodine, vitamin D, and folate – critical for cognitive development, immune function, and long-term health.

This contradiction lays the ground for a new policy review by the Zero Hidden Hunger EU project, funded by Horizon Europe. The analysis shows that hidden hunger remains a persistent and underestimated challenge across the continent. It affects health, productivity, and social fairness underscoring the need for more coordinated and equitable nutrition policies.

Who is most at risk?

Micronutrient deficiencies do not affect all population groups equally. Children and adolescents are particularly vulnerable due to increased nutrient needs during rapid growth, combined with diets often dominated by processed foods. Women of reproductive age frequently experience iron and folate deficiencies, with lifelong implications for maternal and child health. Older adults face risks linked to reduced appetite, medication use, and reduced absorption lead to common deficiencies of vitamin D, calcium, and B12. Low-income households often rely on cheaper but nutrient-poor foods, while people living in low-UV regions – particularly in northern Europe – struggle to maintain adequate vitamin D levels. Migrants and marginalised groups frequently face additional cultural and economic barriers to healthy diets.

These overlapping vulnerabilities can create a cycle of disadvantage that extends across generations.

Europe’s approach to food fortification

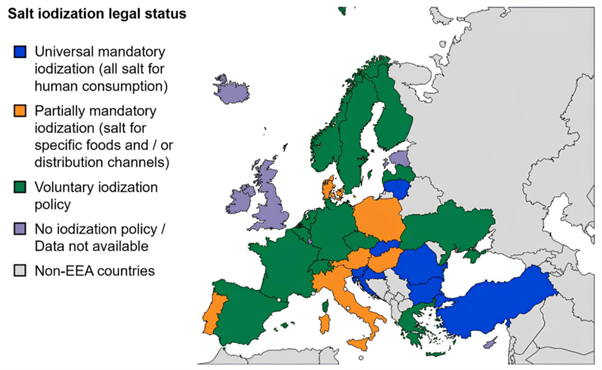

Food fortification is widely recognised as an effective strategy to prevent micronutrient deficiencies. However, across Europe, policies remain inconsistent. Only seven out of thirty-three countries enforce mandatory universal salt iodisation. Six others apply partial measures such as iodised salt in bakeries or school meals. The rest rely on voluntary schemes or have no active measures in place.

Fortification policies for nutrients beyond iodine are similarly fragmented. Only a small group of countries – including Austria, Belgium, Finland, Poland, Sweden, and the UK – require the fortification of selected with nutrients like vitamin D, folic acid, or iron. Elsewhere, fortification remains voluntary, As a result, the type of foods fortified, the nutrients added, and the levels used vary widely from country to country. Vitamin D enrichment is among the most common practice, but coverage remains uneven.

The EU’s role: balancing harmonisation and flexibility

At the European Union (EU) level, Regulation (EC) No 1925/2006 provides the framework for fortification policies. It defines which vitamins and minerals can be added to foods and establishes procedures for the evaluation and authorisation of new nutrient sources. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) plays a central role by providing independent scientific advice evaluating the safety and bioavailability of nutrient sources, and advising on appropriate intake levels.

Article 11 allows Member States to adopt national mandatory fortification programmes – flexibility which, in turn, can lead to policy divergence. One example is the 2004 Commission v. Netherlands case (C-41/02), where the Court ruled that overly restrictive national requirements for fortified foods violated the EU law. Finding the right balance between national autonomy and EU-level coherenceis central to create an effective, equitable nutrition policy across Europe.

Success story: Finland’s vitamin D turnaround

Finland offers a strong example of evidence-based policy in action. Initially relying on voluntary vitamin D enrichment of dairy and fats, Finland doubles fortification levels in 2010 and made fortification of all skimmed milk mandatory in 2016. Within a decade, the share of adults with vitamin D deficiency dropped significantly.

This case demonstrates how regular monitoring and policy adjustment can deliver meaningful public health benefits.

The social dimension: when nutrition meets equity

Hidden hunger is not only a health issue but also a social justice challenge. Programmes that support food security and empower individuals to make healthier choices can indirectly improve micronutrient intake.

At EU level, the Fund for European Aid to the Most Deprived (FEAD), now integrated into the European Social Fund Plus (ESF+), provides food aid through e-vouchers that increase autonomy and reduce stigma.

National initiatives reinforce this trend: Estonia’s Foodcard programme replace standardised food parcels with debit cards that encourage the purchase of fresh produce.In France, ANDES solidarity groceries combine affordable food access with nutrition education and community support.

These approaches show that dignity and choice are powerful for better nutrition.

Barriers to progress: why are we still falling short?

Despite strong evidence and successful examples, Europe’s response to hidden hunger remains uneven. National policies differ widely, creating gaps in coverage and inconsistent implementation. Long-term monitoring systems are limited, with only a few countries routinely tracking the impact of fortification programmes.

Because most schemes are voluntary, industry participation varies, meaning many vulnerable groups are still hard to reach. An equity focus is often missing, and coordination between health, agriculture, and social sectors is often weak. Even front-of-pack labels such as Nutri-Score, which guide consumers on sugar, fat and salt, overlook micronutrient content and therefore miss an opportunity to promote nutrient-dense foods.

A roadmap for a micronutrient-secure Europe

The review highlights several steps that could substantially improve micronutrient status across Europe:

- More harmonised and, where appropriate, mandatory fortification of staple foods could address the most widespread deficiencies(including iodine, vitamin D, folate, and iron).

- Policies should be designed with equity at their core, ensuring that low-income groups, migrants, and rural communities are not left behind.

- Stronger, long-term monitoring systems, including biomarker data, to track progress and refine interventions.

- Updating nutrition labelling systems to incorporate micronutrient content, helping consumers to make more informed choices.

- Closer links between nutrition and social protection policies, with meaningful involvement of civil society, industry, and vulnerable groups.

Conclusion: hidden hunger as a matter of justice

Hidden hunger remains a significant public health issue in Europe, with consequences that extend across generations. The evidence is clear and the policy tools exist: fortification, education, and equitable social support. What remains is the will to act coherently and collectively.

The challenge now is ensuring coordinated, evidence-based action across sectors and countries. As the Frontiers in Nutrition review concludes, “Tackling hidden hunger is not only a matter of health promotion but a moral imperative – a prerequisite for achieving social justice, economic resilience, and a sustainable, inclusive Europe.”

Author: Suzan Otay

Suzan is a policy trainee at the European Public Health Alliance (EPHA) with a MSc in Nutrition and Food Systems from Ghent University. Her interests lie in the interplay between food systems, health, and nutrition policy. Within EPHA, she supported the policy review mapping micronutrient-related policies across Europe and helped develop the project’s Policy Lab methodology and design. She is also involved in broader advocacy initiatives linking health and the environment.